The Immigrants Who Created American Whiskey

Historically, Scottish, Irish, and English immigrants were credited with building America’s spirits industry. Which made a lot of sense, since distillers in Great Britain had produced spirits for centuries. But the truth is more complex and nuanced—in addition to the crucial toil of enslaved workers (see pages 72 and 73 ), America’s distilling industry owes a great debt to a number of major immigrant groups who helped refine and create the main whiskey varieties we know and drink today.

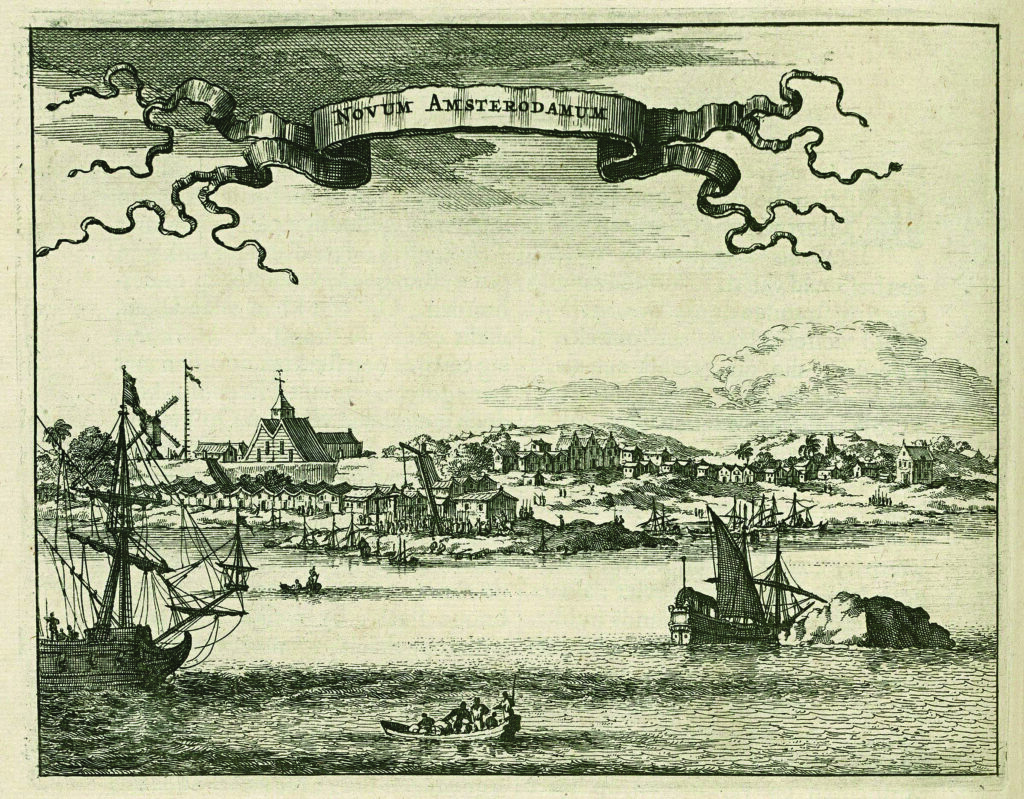

The Dutch

From Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan to the Spuyten Duyvil section of the Bronx, all over New York you can still find traces of America’s early Dutch roots. The area was claimed by the Dutch Republic in the early 1600s and was controlled by the Dutch until 1664. You may be asking yourself What the hell do the Dutch have to do with American whiskey? Well, the answer is more than you realize.

The Dutch built one of the earliest distilleries in New Amsterdam, which was located on Staten Island in the middle of New York harbor. What did it make? Probably all kinds of liquor, including grain-based spirits. No matter what they produced, it was made to drink immediately, so none of it was barrel aged.

The production of grain-based spirits in New Amsterdam makes sense because the Netherlands is, of course, famous for its signature spirit, genever. But in the United States today genever is usually talked about in the same breath as gin. Yes, British gin is based on Dutch genever, but there are key differences between the two spirits. Gin is now made from a neutral base of grain alcohol, usually a wheat or corn spirit that is basically vodka, which is then infused with a range of potent botanicals, including juniper. Genever, on the other hand, was historically made from malted barley and other grains, including rye. And the botanicals aren’t the star of the show here, but instead it’s the grain spirit flavor. If you didn’t know what you were drinking, you’d think it was some kind of unaged or young whiskey.

The experience and knowledge of making genever no doubt informed American distillers for decades. In many ways the Dutch spirit led not only to the British-made gin, but also to whiskey industry in the US.

The Germans

Given that Germany and the Netherlands are neighbors, it should come as no surprise that they shared distilling knowledge. Germany is also one of the world’s biggest producers of rye grain, and the country has a tradition of turning it into a spirit called korn (from kornbranntwein). This spirit, almost unknown in the United States, is one of the forbears of American rye whiskey.

In a 1648 letter found in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Emmanuel Downing asks John Winthrop for his help making German whisky from rye and corn. “I have even now sold my horse to James Oliver for 10l to purchase the still, I pray remember me about the German receipt for making strong water with rye meall without maulting of the Corne, I pray keepe a copie, in Case the noate you send me should miscarye.” This note, according to drinks historian David Wondrich, is incredibly important because it’s the first reference in the North American colonies to making rye whiskey. (It was also written well before people began producing bourbon.)

German immigrants became so known for whiskey distilling expertise that a want ad for “a person who understands the process and management of distilling whisky,” that ran in the Philadelphia Inquirer on December 3, 1794, even specified “A German will be preferred.”

Adding to the legacy of German immigrants is that many of the most famous American whiskies were created by Germans in America, including the talented and prodigious Beams. The family’s influence was so vast that it used to be said that you couldn’t have a distillery without at least one Beam on the payroll. For example, John Henry “Jack” Beam started Early Times, Charles L. Beam was master distiller for Four Roses, and when Heaven Hill opened in 1935 in Bardstown, Kentucky, a Beam—Joseph L. Beam in this case—was making the whiskey. (A Beam family member made the whiskey at Heaven Hill until fairly recently.) At last count there were eleven Beam family members in the Kentucky Distillers’ Association’s Bourbon Hall of Fame.

The Beam name was originally “Böhm,” and all the modern distillers who consider themselves descendants can be traced back to one man: Johannes Jakob Böhm, later known as Jacob Beam. As far as we can tell, he likely came from Germany in the 1750s as a baby, although some believe he was born in southeastern Pennsylvania to immigrant parents. Either way, he no doubt spoke German and was familiar with Germanic drinking and food customs and culture.

Tennessee whiskey George Dickel was created by George A. Dickel, who hailed from Grünberg, Germany, and Old Overholt was created by Henrich Oberholtzer, the son of German immigrants. (His last name later became Henry Overholt.) Isaac Wolfe Bernheim (see the sidebar, pages 110–111) and his brother Bernard Bernheim came from Schmieheim (Baden), Germany, and went on to build a vast whiskey empire. And there were dozens and dozens of other distillers and liquor entrepreneurs who were German immigrants, or their children, often in Ohio, Pennsylvania, or Kentucky.

With the onset of World War I and then the horrors of World War II, many Americans tried to distance themselves from their Germanic roots, changing their names and family histories to leave out that heritage. In whiskey, it was no different. The narrative for the spirit was carefully edited, so the credit for distilling went to Scottish and Irish immigrants instead of Germans.

European Jews

The influx of Jewish immigrants to the United States in the 1800s completely changed the country and also revolutionized the liquor industry. Jews brought with them hundreds of years of distilling knowledge and alcohol business acumen. Thanks to their dietary laws, kashruth, Jews have traditionally produced their own alcohol. In addition, in the 1800s in a number of Eastern European countries, Jews ran the local taverns and distilleries.

During the 1800s and 1900s, Jews fled to the United States to escape anti- Semitism and to find a better life. Through Jewish immigrants already in the US, these new arrivals found jobs in the whiskey industry. Some, like Isaac Wolfe Bernheim, who left Germany, became fabulously successful and wealthy. In fact, there were so many Jews working in the liquor industry that many noted anti-Semites, including Henry Ford, supported a national prohibition of making and selling alcohol, in the form of a constitutional amendment, as a way of depriving these immigrants of a means of making a living and driving them from the country.

While Prohibition shut down the liquor industry outright, it thankfully didn’t have the effect of forcing Jewish Americans to leave the country. And once Prohibition was repealed, Jews played an even more important role in the history of whiskey. Many of the biggest liquor companies were owned by Jews, including Schenley, Seagram’s, and Jim Beam. While Schenley and Seagram’s are no longer around, and Suntory bought Jim Beam, Jewish families still own Heaven Hill and Sazerac. There’s also a new generation of Jewish distillers running craft distilleries across America.